In English literature lessons at school we learn about the ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ or the reader’s ability to go along with made-up writing.

A similar thing happens when people read journalism and other forms of factual writing. No ,it’s not made up (or not very often) but the reader still needs confidence in order to believe. Print/text journalists in particular are up against it, given that their trade is frequently found to be one of the least trusted. So there is a bond of trust between the factual writer and the reader, and the aim is to maintain it.

You can break that bond of trust in many ways, and some of them are quite easily done. If your punctuation is ropey then someone is going to see that mis-used or absent apostrophe and start wondering. If the writer cannot be trusted to get right the basics of the English language, then what else have they failed to check? If they cannot spell, can they be trusted to deliver facts? If they get one fact wrong, who’s to say the rest of the facts are correct?

Here’s a little example I use with undergraduate students: “you’re writing about sailors, on a submarine, and how their ship got in trouble. Then, they were saved by some soldiers from the Royal Marines on a nearby boat.” All good? No: submarines are boats, not ships, although I believe* most other floating vessels apart from submarines are in fact ships. Marines, by the way, are not soldiers, but Marines.

It’s not pedantry but just respect for accuracy and the people who are giving their time, and sometimes money, to read your stuff. Ignore accuracy and readers will find that bond of trust broken. Then they will read instead someone who appears to care about getting it right.

*The starting point is to accept that we don’t know everything. How on earth, for example, do you refer to a police officer with a complicated title that doesn’t bear repeating in text too often? Detective Chief Superintendent Jane Whatever; then Det Chf Sup, or what? How to spell words that originate in other languages? Al Quaeda? That’s just a guess. But don’t guess. Instead, where there’s doubt and even where there’s a choice, be guided by those who have really thought about these things. They write (and re-write) style guides in order to deliver complex and messy things as elegantly as possible. One of the best and, surprisingly, the funniest, is that of the Guardian.

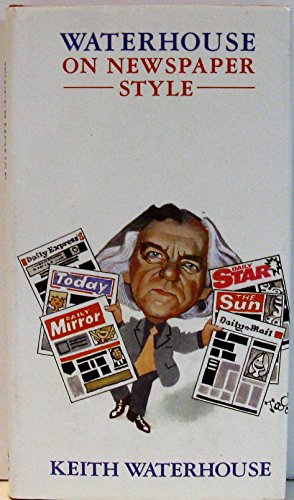

Finally, if you can get hold of it, try Keith Waterhouse’s book.